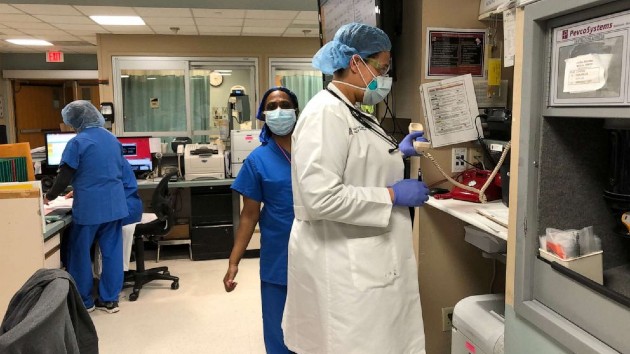

Dr. Elizabeth ClayborneBy RACHEL SCOTT and BRIANA STEWART, ABC News(CHEVERLY, Md.) — In a Maryland emergency room under siege by the coronavirus, three pregnant doctors are fighting to save patients, while protecting the lives growing inside them.Dr. Elizabeth Clayborne, Dr. Tu Carol Nguyen and Dr. Michele Callahan are expecting mothers and physicians on the front lines of the emergency department at the Prince George Hospital Center in Cheverly, Maryland. The medical facility has seen an uptick of COVID-19 patients following a surge of cases since early April.“I’m definitely visibly pregnant now, so as soon as I walk in the room, a lot of people are like, what are you doing? Why are you here?” Clayborne told ABC News.“Well, I’m Dr. Clayborne and I’m here to take care of you today,” she often replies.Months before there were known U.S. coronavirus cases Clayborne, Callahan and Nguyen realized they were all expecting their second child around the same time.“We were excited and then we found out we’re all having girls, having summer babies. So we’re really giddy and excited about this experience and we’re going to share as mothers,” Clayborne said.But when the pandemic hit, they felt a call of duty to stay on the front lines, six to seven months pregnant.“We sat down, actually, the three of us as a group to talk about what we wanted to do. We decided that we were going to continue working to support our colleagues, we knew that they were going to need our help,” Clayborne said.”It’s what we signed up for, and we want to be there or else we wouldn’t be there,” Callahan said.Management at Prince George’s Hospital Center told the doctors they could take an unpaid leave of absence, encouraging them to take it one shift at a time.“We do have a policy where our physicians have the option, particularly those who are expectant mothers and those who are in other vulnerable populations, to not work on the front lines. But we definitely [appreciate] those workers who choose to stay and their bravery is definitely applauded and we’re so thankful,” Jania Matthews, senior director of media relations and corporate communications at the University of Maryland Capital Region Health, said.Their colleagues have also stepped up to perform medical procedures like intubations on their behalf, in hopes of limiting their exposure to severely ill patients.Even with the added support and personal protective equipment, close contact with patients has become nearly impossible as cases spike throughout the state.At the epicenter of Maryland’s COVID outbreak: Prince George’s CountyWith an upswing in cases, Prince George’s County has become the state’s hotspot with more than 4,000 COVID-19 cases, the most of any county in the state.To meet the new demands, Prince George Hospital Center has set up tents outside the medical facility to accommodate more patients. The administration has also opted to cancel elective and procedural surgery to free up staff and beds.“I worked a shift last week and realized that almost all the patients that were surrounding me in the immediate area were COVID positive. And that’s an unprecedented experience to have as a provider,” Clayborne said.Serving in a majority-black county, Clayborne said she has seen firsthand the alarming impact on African American residents.To date, blacks make up 37% of coronavirus cases in Maryland, comprising 5,550 cases of the 14,775 cases in the state.Emerging reports from states across the country have revealed the pandemic’s significant impacts on minorities.Early data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reveals blacks make up a disproportionate number of fatalities, totaling 33% of overall cases.“When they get sick, they’re getting sick faster. They’re getting more sick and they’re more likely to die. And it really is tragic because we are seeing it play out in such a severe form,” Clayborne said.As the number of cases spike, the doctors are inching closer to their due dates. Each day, they individually weigh their decision to continue to work.“I’m getting a little more nervous because the number of sick COVID positive patients that we’re seeing is increasing and it’s becoming more difficult for me to not see the sick patients and do not have to do procedures like intubations,” Clayborne said.Still, she is on a mission to help lessen the impact of the health disparities and soften the mistrust of the medical system among minority communities.“When they see a face like mine, where they hope that I identify with their struggle, that I understand why they have a mistrust of the system — we are starting to build some bridges,” Clayborne said.On the frontlines while expecting: “I’ll feel her kick” during patient examinationsBeing on the frontlines while expecting is not without frequent trips to the bathroom, shortness of breath and the occasional kick from their baby girls inside the womb.“I’ll be like trying to lean over to examine a patient and I’ll feel her kick. And I’m like, oh, I’m not here by myself,” Clayborne said.The personal protective equipment critical for doctors in the battle against coronavirus can be uncomfortable for the women as they continue to work through their pregnancies.“When you’re wearing these N-95 masks or anything else, it’s basically you’re being suffocated for like 10 hours, 11 hours a day,” Callahan said.With their faces covered for hours, staying hydrated and nourished has proven to be a challenge.“Because we’re wearing N-95 masks like constantly, I do forget to drink water. And then I’m like, oh, I’m feeling really parched,” Nguyen said.Expecting mothers face anxiety with limited data on adverse outcomes of COVID-19 exposureThirty-four weeks along, Callahan fears being separated from her infant, if she tests positive.“When I go in for labor, they’re going to test me at my hospital. If I test positive, there’s a potential that they’ll take my baby for two weeks,” Callahan said.Limited data on the effects of coronavirus and pregnancy has also brought unease and anxiety for expecting mothers across the nation.“We do not have a lot of data on the relationship of pregnancy, especially early trimester pregnancy, with COVID infection,” Dr. Rahul Gupta, senior vice president, and chief medical and health officer at March of Dimes, told ABC News.“We have tools that do not encourage us to use surveillance and other types of data in real-time and be able to be proactive,” Gupta said.Groups like March of Dimes have stepped up to provide free advice for expecting and new mothers but experts are challenged with a lack of information, raising questions about whether maternal infection could lead to troubling and detrimental outcomes. Even with full personal protective equipment, Clayborne admits she could be exposed just weeks before delivery.“I could not only jeopardize my life but could jeopardize the life of my baby girl who I’m carrying inside of me. And it’s really scary but it’s my kind of natural instinct to go towards problems sometimes and face them head-on,” Clayborne said.Even after being surrounded by death and pain, there are moments of joy about the lives they will soon bring into the world, the playdates their girls will share and the example they hope to have set.“There’s always going to be challenges that lie ahead in her life and the lives of human beings forever and always. And so how we respond to those challenges is really important. And I hope that she likes the example that I gave her of rising to the occasion,” Clayborne said.

Copyright © 2020, ABC Audio. All rights reserved.